I secretly harbor feelings of street-punk activism, imagining myself spraying stencils and slapping up stickers (the quickie methods) to protest rampant over-development, strip-mall sprawl, and billboard advertisements that pollute more than any tag ever could, I hold myself in check. Mostly because I'm too scared and lazy to run through the streets, spray can in hand. I've also been on the other side of the matter, diligently painting over multiplying scrawl-tags on my house and neighbors' houses (tags will spread like tribbles on the Starship Enterprise if you ignore them). In this manner, I kept the residential vandalism in check but no matter what we do or how we feel about it, graffiti isn't going to stop any time soon. Those are two sides of the issue. After you see Bomb It, you'll never think about graffiti in simple terms again.

Paintings on walls—an ongoing theme.

|

| Chauvet cave paintings in France from approximately 35,000 years ago |

And now:

We begin in Philadelphia, where legend has it, modern day graffiti as an obsessive and known quantity began. Meet Darryl McCray, aka "Cornbread," prolific tagger and ex-reform-school kid, who once was arrested for tagging the side of an elephant at the city zoo. As cruel as it was, from a graffiti standpoint, that's some bragging rights right there. Cornbread wasn't affiliated with any street gangs—his tags were his own.

|

| Cornbread "King of the Walls," in Philadelphia, 1967 |

When I think of graffiti, I immediately recall visiting New York city several times in the mid-80s and and marveling at the subways. Summer time and you'd be waiting in a station in hundred-degree heat, feeling like a baked potato in a brick oven, when VOOM, along comes your train and it's just COVERED in art. Dazzling, vibrant, completely unexpected art. You never knew what you'd get. Maybe a plain train--pristine, silverish-gray, utilitarian but dull, or a tremendous day-glo dragon, staring you down as you entered its interior. It was completely up for grabs and it was often marvelous.

|

| Lady Pink apologizes to her mom for painting on the subway |

Interviews with now-middle-aged artists of the time reveal most were from the outer boroughs, poor, without playgrounds, yards or greenery, not a lot of career prospects in the neighborhood, who sought to express themselves among a crumbling infrastructure.

The Bronx in a bankrupt city.

Youthful taggers show their stuff.

Wild style lettering, created at this time, is likened to jazz improvisation.

|

| Lady Pink, first lady of graffiti art, is one of several pioneering artists interviewed |

As New York City cleans itself up (several interviews come from the side of "The Man," without judgment—a sign of high-quality documentation), graffiti artists have literally gone underground.

|

| Revs writes his stories in the tunnels below New York City |

The point is made—a valid one—that unchecked self-expression leads to an impression of systematic neglect on our city streets. It's interesting to note that systematic neglect inspired many street artists in the first place.

|

| I personally find this uninviting but I do miss the art cars of the 80s |

So that's my go-to think-place for graffiti—New York City of the 80s, but there's an entire world of street art to explore and Bomb It sets out to do so. As with any art form, culture, architecture, history and current state-of-affairs all contribute to the movement.

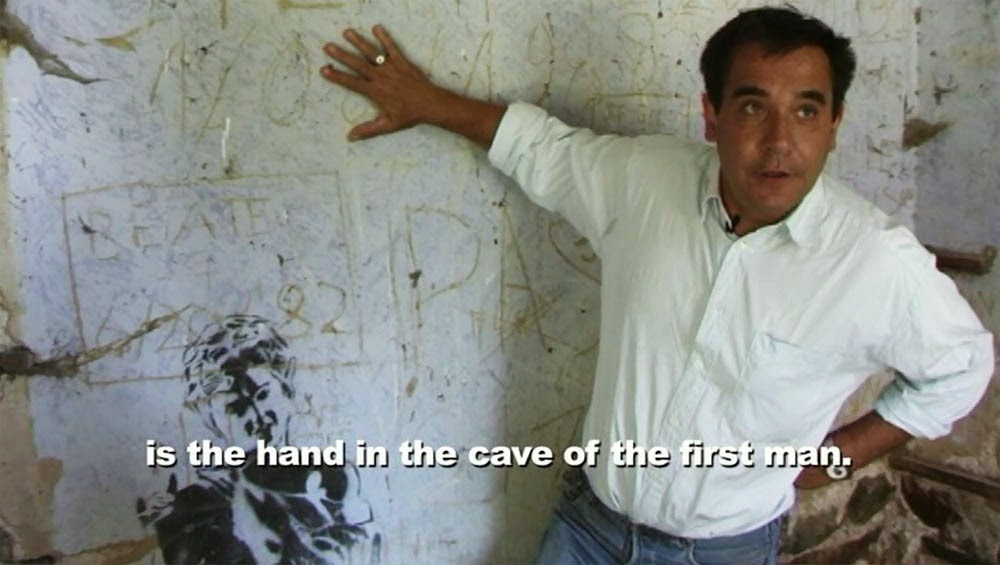

Over in France, there's Blek le Rat, who as a young man, strove to cover all of Paris with rat stencils. I feature a lot of Blek here because if you wanted to contrast different attitudes and backgrounds regarding city graffiti at their most extreme, you couldn't do a better job than New York City of the late 20th century and middle-aged Blek in France today. He doesn't just paint walls, he philosophizes over them as well.

Blek could not be more French in concept or tone. In case you missed his artful stance, he ties in stenciling to the dawn of self-expression.

I conclude by saying: Blek—c'est magnifique! But there's more to France than lyrical musings. There's income disparity, homelessness and racism. All are addressed here from a graffiti standpoint.

We get more fascinating musings on guerrilla artwork in Amsterdam, Berlin, London, Barcelona, São Paulo, Capetown and Tokyo. People who run around in the middle of the night spraying public areas with paint are definitely an interesting, often quite thoughtful group. Reiss had to hone down hundreds of hours of footage, shot by his amazing cinematographer, Tracy Wares, for a feature film. The result is so rich, you can return to it over and over and gain new knowledge—it's crammed full of insight. It takes multiple viewings to absorb it, digest it, live with it.

Surprisingly, more than one artist points out that defacing homes, schools and churches is not cool. Another forgives tagging because, (I paraphrase) "It's how the kids start out, before learning new skills." There's a well-rounded humanitarian concept to the enterprise.

Here's Mickey in Amsterdam. She's an elementary-school teacher who's come out as an underground painter with years of experience.

How protective are you about this particular wall in Berlin? Do you think a respectful "hands-off" anti-graffiti stance was warranted here? After all, it is a government wall.

A quick reference to Banksy in London illustrates the culture of surveillance we live under.

South Africa has a history of political graffiti and instant imprisonment without legal representation or trial if a painter was caught. Again, we ponder, is graffiti outright vandalism under tyrannical rule?

In Capetown, the residents of this township didn't have the means to buy paint, so the artists came to them.

In Barcelona, a discussion among neighbors covers both sides of residential graffiti. One dismisses it entirely. The other says it beautifies the neighborhood. Figurative art is heavily featured.

São Paulo is a thoroughly fascinating world of art among the decay. Where police are so busy dealing with serious issues, they let graffiti artists paint with impunity (at this filming). Where graffiti is a visceral response to impending dystopia that unfolds before our eyes, from the tops of buildings, to the sewage tunnels beneath the surface. Several novels could be written based on the Brazilian footage alone.

The gallery co-opting of graffiti is touched upon just enough to show how iffy a prospect it is to display street art in a museum setting. Eyed by patrons instead of the general public, street art loses its power to startle and comment on modern life. It becomes an object for sale, losing its original intention. Merchandising has a long tradition too. If artists can turn their art into a living, I say: GOOD, keep going.

Jon Reiss is a man of action. There's already Bomb It 2, covering more of the world of graffiti. I won't wait so long to see it.

No comments:

Post a Comment